Factors Contributing to Behavioural Concerns

The people we support may be in situations where they are not full members of their communities because of the behavioural concerns. Individuals being referred to Valor & Solutions’ clinical services present with challenging behaviours and complex needs that impact their overall quality of life.

Currently, there is no universal definition of behaviour problems, however Tassé & collab (2010) define it as actions that are judged as problematic because they defy social, cultural and developmental norms, and are damaging to the person and their social or physical environment. They define severe behaviour problems as a behaviour that puts the individual or others at potential or actual physical or psychological risk, or that places the environment at risk and/or compromises the person’s freedom and social integration.

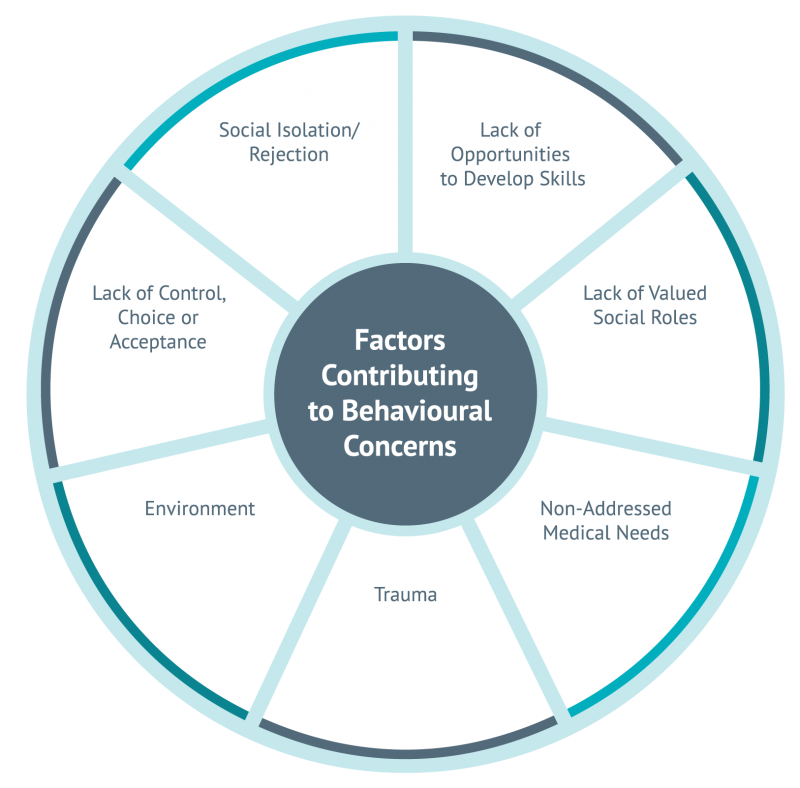

Many factors can contribute to these behavioural concerns:

References

Balogh, R., Ouellette-Kuntz, H., Bourne, L., Lunsky, Y., & Colantonio, A. (2008). Organising healthcare services for persons with an intellectual disability (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue No. 4, 1-39.

Berney, T., & Allington-Smith, P. (2010). Psychiatric Services for Children and Adolescents with Intellectual Disabilities. Royal College of Psychiatrists. College Report CR163.

Emerson E., & Einfeld S.L. (2011). Challenging Behaviour (3rd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fletcher J.M., Lyon G.R., Fuchs L.S., & Barnes M.A. (2007). Learning Disabilities: From Identification to Intervention. New York: The Guilford Press.

Joyce, Theresa. (2006). Functional Analysis and Challenging Behaviour. Psychiatry, 5(9), 312 -315.

Lennox, N., Taylor, M., Rey-Conde, T., Bain, C., Boyle, F., & Purdie, D. (2004). Ask for it: Development of a Health Advocacy Intervention for Adults with Intellectual Disability and their General Practitioners. Health promotion international, 19(2), 167-175.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2015). Challenging Behaviour and Learning Disabilities: Prevention and Interventions for People with Learning Disabilities whose Behaviour Challenges (NICE Guideline). NG11, 1-59.

Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health. (2012). Evidence In-Sight Request Summary: Trauma in Children and Youth with Dual Diagnosis. Evidence In-Sight Report, May 2012, 1-13.

Pitonyak, David. (2007). Toolbox for Change: Loneliness is the Only Real Disability. Dimagine, 14.

Tassé, M.J., Sabourin, G., Garcin, N., et al. (2010). Définition d’un trouble grave du comportement chez les personnes ayant une déficience intellectuelle. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 42(1) : 62–69

Wolfensberger, W. (1998). A Brief Introduction to Social Role Valorization: A High-Order Concept for Addressing the Plight of Societally Devalued People, and for Structuring Human Services. (3rd ed.). Syracuse University, New York: Training Institute for Human Service Planning, Leadership and Change Agency.